Many of Woodlawn’s most imposing monuments may be taken as glorifications of a powerful family dynasty or displays of wealth and status — but many are also monuments of love. Commemorations of loved ones who have passed, they are reminders of what we come to cemeteries for, and stories of love, in all its different forms, also tell us about the full and diverse lives of those who have lived and loved and died here…

George Campbell Taylor and Betsy Head

George Campbell Taylor was the son of a wealthy merchant and banker from whom he inherited an income of $20 million. While traveling in Europe, George met Betsy Taylor and took her and her daughter to America, where Betsy became his housekeeper and common-law wife.

George bequeathed one million dollars in real estate to Betsy as well as a million more in bonds and stocks, but she died three months before him in 1907. They were ultimately buried in separate lots for the sake of propriety at the time, but had mausoleums with matching windows.

In an ironic twist, George and Betsy were reportedly furious when Betsy’s eighteen-year-old daughter Lena married their gardener, and disinherited her entirely. One can only speculate why and take from it the suggestion that many of these stories are more complex — and more political — than meets the eye…

Jack Pickford and Marilyn Miller (Olive Thomas’ grave)

Jack Pickford and Marilyn Miller (Olive Thomas’ grave)

Love has been discovered upon occasion at Woodlawn, when grieving individuals encounter one another on our grounds. Following the tragic losses of their spouses, Broadway star Marilyn Miller and film actor Jack Pickford, brother of silent film star Mary Pickford, met while they were building private mausoleums. Miller was mourning the loss of Frank Carter, who had been killed in a car accident, and Pickford was grieving for Olive Thomas, who had died after accidentally consuming mercury bichloride.

Pickford and Miller married in 1922, at “Pickfair,” the famous Hollywood home of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, with many showbiz notables in attendance. Images of the celebrity couple were featured in all the tabloid papers. Unfortunately the marriage didn’t last, with the couple divorcing on grounds of incompatibility, but both Miller and Pickford went on to find love again. In a statement from Pickford, he remarked: “We are as good friends as ever and the divorce is a matter of mutual consent. I have only the highest regard for Miss Miller. She is a splendid actress and I wish her nothing but the greatest success.”

In an intriguing aside, the mausoleum of Olive Thomas also contains a drawer intended for Jack, but it remains unfilled to this day as he was buried in California at his sister’s insistence. Miller was buried with Frank Carter in the mausoleum she had constructed for him.

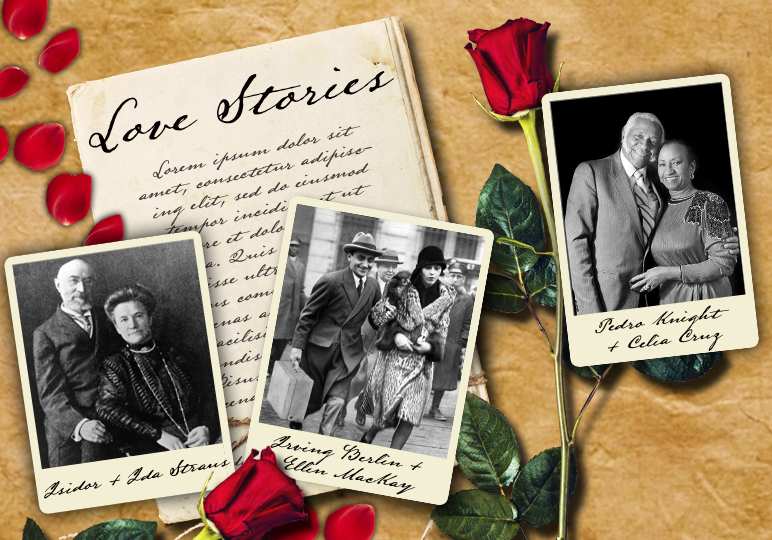

Celia Cruz and Pedro Knight

Celia Cruz and Pedro Knight

“Queen of Salsa” Celia Cruz and Pedro Knight were married for 41 years before Cruz’s death in 2003 of brain cancer. Both prominent performers in the rising salsa genre, Celia and Pedro met in Havana in 1950 when Celia joined the popular Sonora Matancera Orchestra, in which Pedro played the trumpet. They defected together with the orchestra in 1960 at the time of the Cuban Revolution and moved to the U.S., where they were married in 1962. Pedro later abandoned his own professional trumpet-playing career to act as manager for his wife, who became a global salsa star. They often appeared on stage together, and Celia fondly referred to him as “Little Cotton Head” for his head of snowy white hair.

When Celia died, Pedro commissioned a mausoleum specifically designed to be accessible to all visitors. He had two clear glass windows built in so fans could look in and admire the ornamented interior of the mausoleum, which includes a stained-glass window depicting Our Lady of Charity, the patron saint of Cuba. Pedro also loved to spend time with fans had come to pay respects to Celia, and delighted in sharing memories of his beloved wife.

In 2007, Pedro passed away and was entombed beside her on February 13th, just one day before Valentine’s Day. When Celia’s former manager was looking for photos of Knight to decorate his tomb, he said that it was difficult to find a picture of just him alone, as “they were always together.”

Bernard Moritz Philipp and Jane Peterson

Bernard Moritz Philipp and Jane Peterson

Investment banker and art collector Bernard Mortiz Phillip and painter Jane Peterson married when he was eighty and she fifty. The couple lived in an exquisite five-story home on Fifth Avenue which had a sky-lighted studio for Jane on the top floor and was located across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The door of their shared mausoleum replicates the front of their home, and if you look closely at the mausoleum, there are portraits of the couple hidden in the top of granite columns that frame the entry. Although Moritz Phillip died only four years after their marriage, such gestures suggest that theirs was a very successful marriage.

Investment banker and art collector Bernard Mortiz Phillip and painter Jane Peterson married when he was eighty and she fifty. The couple lived in an exquisite five-story home on Fifth Avenue which had a sky-lighted studio for Jane on the top floor and was located across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The door of their shared mausoleum replicates the front of their home, and if you look closely at the mausoleum, there are portraits of the couple hidden in the top of granite columns that frame the entry. Although Moritz Phillip died only four years after their marriage, such gestures suggest that theirs was a very successful marriage.

Stories conflict, however, as to his effect on his wife’s career. Peterson had previously painted a good deal of avant-garde work featuring undomestic subjects such as military portraits, war scenes, and street scenes, but some accounts have it that her husband asked that she confine her focus to paintings of floral arrangements, considered more appropriately feminine. On the other hand, Peterson did have a natural love of flowers, and after his death would continue to focus on the subject, as well as landscapes, for the rest of her life.

Lawrence and Elvira Rosini-Wegielski

This special mausoleum was constructed by Lawrence Wegielski in honor of his wife, Elvira “Ve-Ve” Rosini Wegielski. The couple ran a liquor store together in Mount Vernon before retiring and moving from Williamsbridge to Stony Point in Rockland County. They would spend every day together up to 13 hours a day. After Elvira died of stomach cancer at age 68 in 1994, Wegielski set about making the most personalized shrine possible to his wife and the 25-year marriage he shared with her.

This special mausoleum was constructed by Lawrence Wegielski in honor of his wife, Elvira “Ve-Ve” Rosini Wegielski. The couple ran a liquor store together in Mount Vernon before retiring and moving from Williamsbridge to Stony Point in Rockland County. They would spend every day together up to 13 hours a day. After Elvira died of stomach cancer at age 68 in 1994, Wegielski set about making the most personalized shrine possible to his wife and the 25-year marriage he shared with her.

First of all, the mausoleum was made in pink granite as Elvira’s favorite color was pink. It is adorned with two snow fountains on either side, and with the inscription Side by Side Baby on each of the benches. Inside, it is decorated with the crystal chandelier from their house as well as other personal mementoes.

Lawrence would regularly visit the grave three days a week, and would play cassettes of her favorite music while having lunch there. He was also in the habit of decorating extravagantly: installing ornamented trees and a talking wreath for Christmas, and hand-painting more than 50 wooden hearts red and silver for Valentine’s Day.

The couple had no children after Elvira gave birth to a stillborn son in 1970. They never went on vacation, and they lived so frugally that by the time Elvira died, they had considerable savings. Elvira actually disapproved of the idea of having a private mausoleum — when Lawrence raised the idea shortly before her death, she replied, “Don’t you dare” — but of course Lawrence went ahead anyway and has since spent lavishly on flowers and ornamentation.

Lawrence went on to find a partner in a widow from Stony Point named Susan Domanico and the couple make visits to the graves of their respective spouses together. He was laid to rest in the mausoleum’s second crypt.

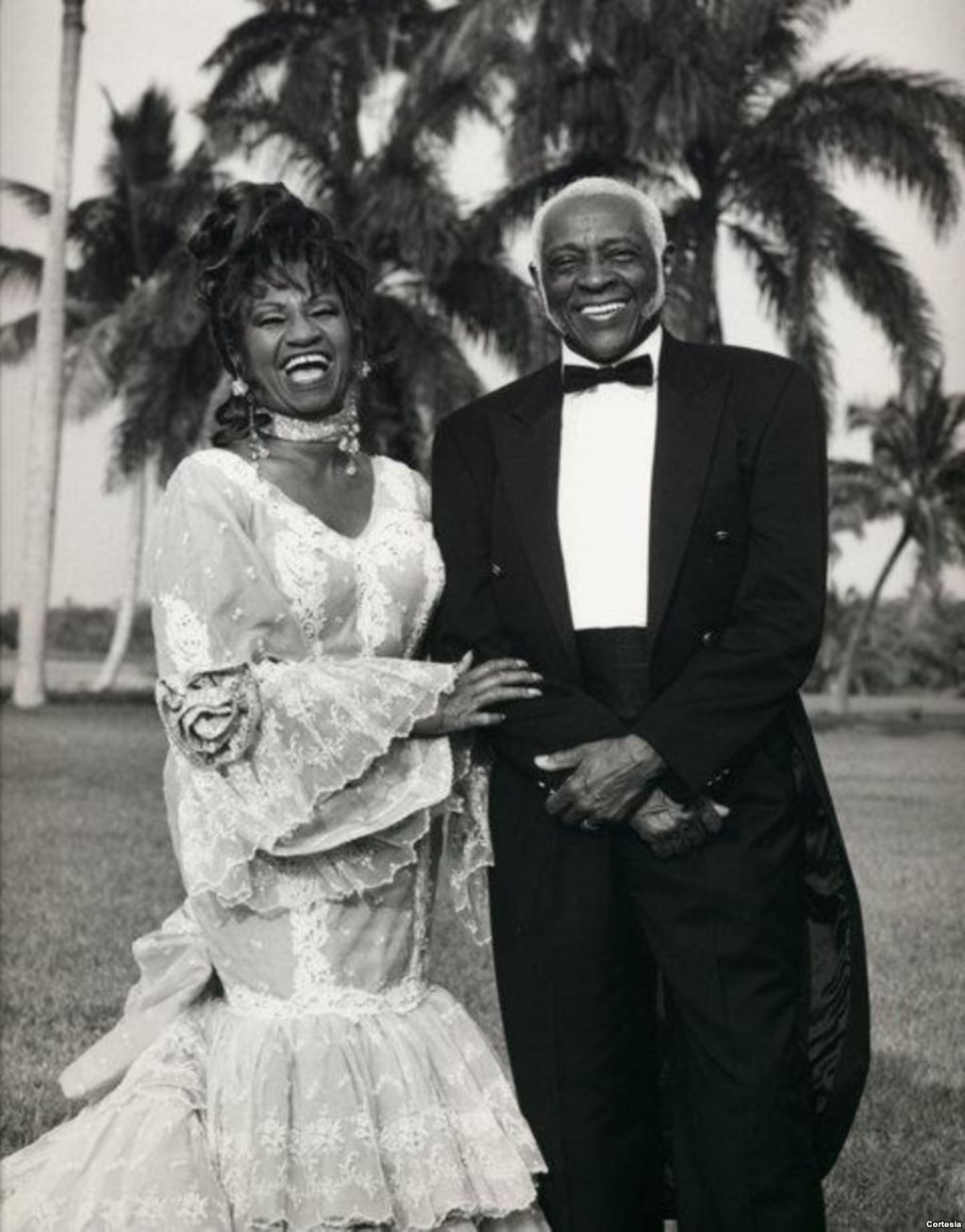

Isidor and Ida Straus

German-American businessman and philanthropist Isidor Straus — most known as the co-owner of Macy’s — met Ida Blun when he moved to New York City following the Civil War. They married in 1871, and went on have seven children and what by all accounts was a sweet and cherished marriage. The couple always traveled together and were rarely apart, writing letters to each other daily whenever they had to spend time away.

German-American businessman and philanthropist Isidor Straus — most known as the co-owner of Macy’s — met Ida Blun when he moved to New York City following the Civil War. They married in 1871, and went on have seven children and what by all accounts was a sweet and cherished marriage. The couple always traveled together and were rarely apart, writing letters to each other daily whenever they had to spend time away.

In 1912, the elderly couple went on a winter vacation in Europe, and boarded the RMS Titanic on its voyage to New York City to make their return home. Isidor was 67 and Ida 63. When the Titanic struck the iceberg, Isidor escorted Ida to a lifeboat and prepared to say goodbye, but Ida refused to board. There are multiple accounts of what she said, and one version has it: “I will not be separated from my husband. As we have lived, so will we die, together.” Rather than choosing to save herself, Ida sent her newly employed maid in her place, after first wrapping her in Ida’s fur coat to protect her against the cold.

As the ship went down, multiple survivors recall seeing the couple standing on the deck, arm in arm.

Isidor’s body was later recovered and his funeral was delayed for a few days in the hopes that Ida might also be found and they could share a funeral service — but Ida’s body was never found. On the day of their funeral, over 20,000 mourners gathered at Carnegie Hall in their honor.

The inscription on the memorial fountain reads: “Many waters cannot quench love neither can the flood drown it.”

Patricia Cronin’s Memorial to a Marriage

Patricia Cronin’s Memorial to a Marriage is easily one of the most striking and beautifully moving sculptures at Woodlawn. The contemporary piece commemorates the relationship between artist Patricia Cronin and her then-girlfriend Deborah Kass, whom she has since married.

Prior to conceiving the work, Cronin visited Woodlawn and was struck by how all the male figures were all cast in their actual likeness, but the female figures were all allegorical personifications of grief, purity or some abstract ideal. Her work, then, is intended as a reaction and a political statement, especially as at the time gay marriage still hadn’t been legalized.

The work was first installed in 2002 as a piece in Carrera marble, but the artist was concerned it would deteriorate over time. In 2011, it was replaced as a new version cast in bronze. Cronin specifically chose the material because viewers could interact with it, and the bronze would take on polished sheen in areas touched especially often.

Cronin commented at the time: “[My partner and I] have wills, health-care proxies, powers of attorney, and all of the legal forms one can have, but they all pertain to what happens if one of us should become incapacitated or die. It’s not about our life together; it’s about the end of it. So I thought, what I can’t have in life, I will have forever, in death.”

Patricia Cronin and Deborah Kass married on July 24, 2011: the day same-sex marriage was legalized in New York. The sculpture was installed the day that gay soldiers were allowed to serve openly in the military.

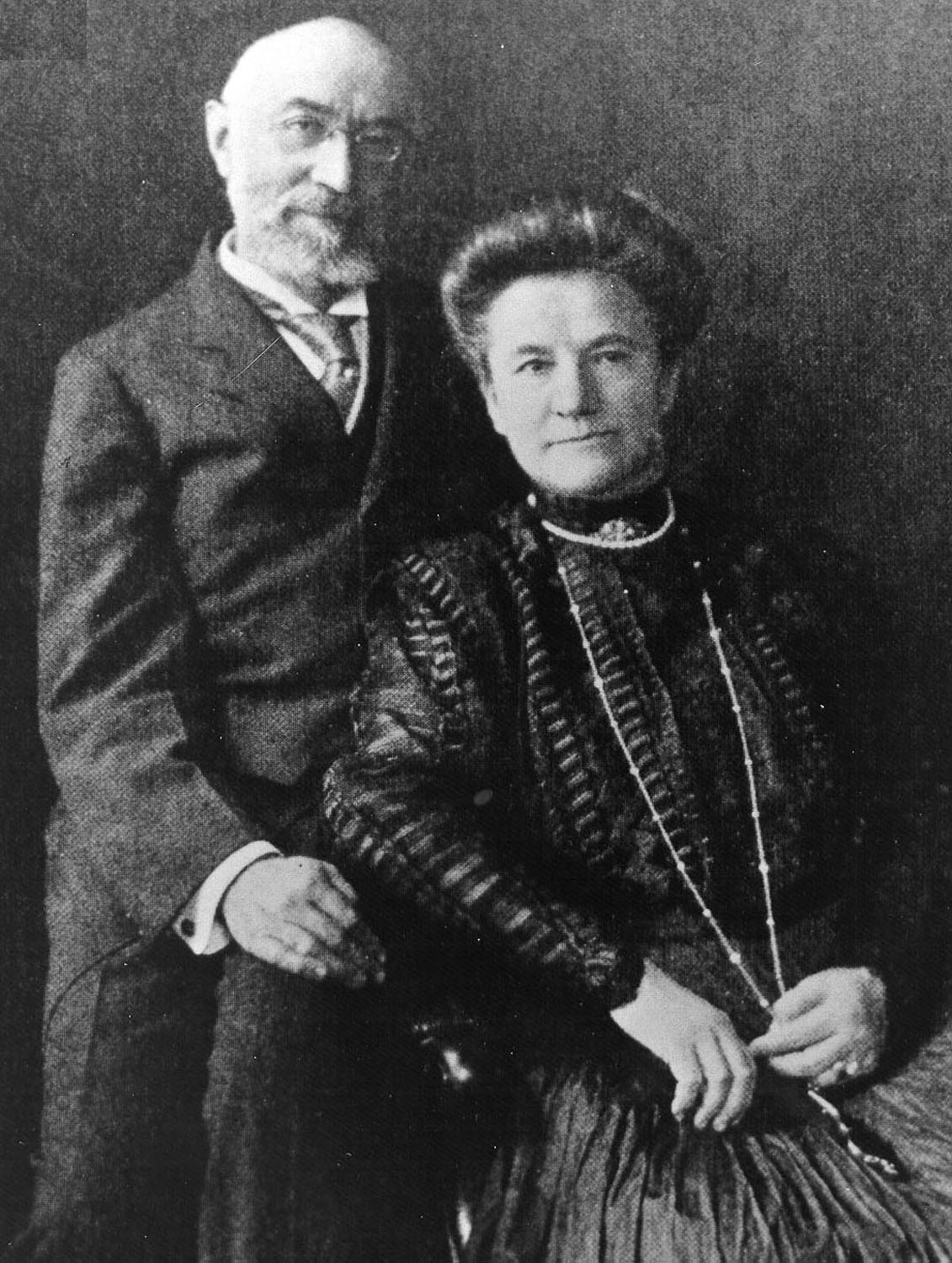

Irving Berlin and Ellin MacKay

When famous songwriter Irving Berlin married novelist Ellin McKay, their unconventional union was considered “one of the most sensational social events of the 1920’s.” Berlin is now considered one of the greatest songwriters in American history, celebrated for hits such as “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”, “White Christmas”, “There’s No Business Like Show Business”, and was already a success at the time of their engagement, but was still scorned by the father of the bride. Berlin was Russian Jewish immigrant from the Lower East Side, as well as a widower 15 years older than McKay. McKay was a Roman Catholic debutante whose multimillionaire father threatened to disinherit her if she married Berlin.

When famous songwriter Irving Berlin married novelist Ellin McKay, their unconventional union was considered “one of the most sensational social events of the 1920’s.” Berlin is now considered one of the greatest songwriters in American history, celebrated for hits such as “Alexander’s Ragtime Band”, “White Christmas”, “There’s No Business Like Show Business”, and was already a success at the time of their engagement, but was still scorned by the father of the bride. Berlin was Russian Jewish immigrant from the Lower East Side, as well as a widower 15 years older than McKay. McKay was a Roman Catholic debutante whose multimillionaire father threatened to disinherit her if she married Berlin.

Mr. McKay even took the step of sending her off to Europe to find other suitors in the hope that she would forget Berlin. But Berlin broadcast love songs he had written specifically for her over the radio, such as “Remember” and “All Alone”, and the couple wrote each other daily.

McKay was also a liberated young woman who had written in an article for The New Yorker on the importance of modern girls marrying whom they choose, “satisfied to satisfy themselves.” She went ahead with the marriage — clearly making the right match as it was to last 62 years. She also reconciled with her father five years later.

Berlin and McKay went on to have a son who died in infancy and three daughters.

Fiorello La Guardia and Marie Fisher

New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia was married twice. His first marriage, to Thea Almerigotti, only lasted three years from 1919-1921 and ended tragically with the death of their daughter, Fioretta Thea, due to spinal meningitis and the passing of his wife due to tuberculosis several months later. In 1929, La Guardia married his long-time secretary, Marie Fisher. They adopted two children, Eric Henry, and Jean Marie, the biological daughter of Thea’s sister. In another act of compassion, upon the death of La Guardia in 1947, Fisher arranged to have the monument honoring his wife and daughter preserved by casting it in bronze. Fisher would go on maintain a public profile, supporting civic groups, political candidates, and philanthropic organizations including the Red Cross and other groups fighting cancer, polio and muscular dystrophy.

Lionel and Gladys Hampton

“King of the Vibes” Lionel Hampton was one of the jazz greats, known for his innovative use of the vibraphone. In 1936, he married Gladys Riddle, who would go on to act as his booking agent, accountant and manager of her husband for decades. Gladys was known as a shrewd, determined, and independent woman: once, Lionel fired the singer Betty Carter, and Gladys rehired her, asserting her own authority.

“King of the Vibes” Lionel Hampton was one of the jazz greats, known for his innovative use of the vibraphone. In 1936, he married Gladys Riddle, who would go on to act as his booking agent, accountant and manager of her husband for decades. Gladys was known as a shrewd, determined, and independent woman: once, Lionel fired the singer Betty Carter, and Gladys rehired her, asserting her own authority.

As Lionel said, “God gives me the talent and Gladys gives me the inspiration.” When Gladys died in 1971 of a heart attack, Lionel was so depressed for a time that he almost stopped performing. He never remarried. Gladys had been involved in the construction of an affordable housing project in Harlem, and Lionel funded the Gladys Hampton Apartments in her name and honor.

Sam and Anne Lewis

Sam Lewis was a prolific Irish-American composer and member of the Songwriters Hall of Fame whose works included Dinah, Mammy, How Ya Gonna Keep ‘em Down on the Farm (After they’ve seen Paree)?, and I’m Sittin’ on top of the World. Lewis fell in love with the young Irishwoman Anne Lewis, and the coupled traveled extensively before settling down in an apartment on the west side of Central Park.

When Anne passed away in 1955, Sam selected a sizeable heart shaped monument. At the base it reads I Heard a Forest Praying, a Lewis composition about life, love and loss.

Cootie and Catherine Williams

Cootie and Catherine Williams

Cootie Williams was a jazz, rhythm, and blues trumpeter who played with Benny Goodman’s orchestra and the Duke Ellington band. When he died of a kidney ailment at age 74 in 1985, his wife Catherine sent an exquisitely moving letter to Woodlawn Cemetery extolling her husband’s fame and importance, and how he deserved a place of honor among the other jazz greats.

Her own grave went unmarked for a time before the Duke Ellington Society added her gravestone.

Alexander and Angelica Archipenko

Alexander Archipenko was a celebrated Ukrainian-American artist and sculptor known for his pioneering work in Cubism. He was an important figure in the movement, working and exhibiting widely in Europe as well participating in the groundbreaking Armory Show in New York.

Alexander Archipenko was a celebrated Ukrainian-American artist and sculptor known for his pioneering work in Cubism. He was an important figure in the movement, working and exhibiting widely in Europe as well participating in the groundbreaking Armory Show in New York.

In 1921, he married German sculptor Angelica Forster. In 1923, the couple emigrated to the U.S., where Alexander taught widely across America and opened several art schools.

When Angelica died at the age of 65 after a long illness in 1957, Alexander chose to feature her art on their shared grave — despite that he was the more renowned of the two — in an act of love and humility. The sculpture is named Premonition, and Alexander gave small ceramic versions of it to friends at her funeral.

Florence Mills and Ulysses Thompson

Florence Mills and Ulysses Thompson

Florence Mills was an African-American cabaret singer, dancer, and comedian billed as “The Queen of Happiness.” She was part of a travelling show of black performers, the Tennessee Ten, when she met her future husband, Ulysses “Slow Kid” Thompson, in 1917. Ulysses was an acrobatic dancer and multi-talented performer in his own right, but chose to dedicate himself to managing and promoting his wife’s career after realizing her talent outshone his.

At age 31, Florence passed away after over exhausting herself through hundreds of performances and contracting tuberculosis. Over 10,000 people came to the funeral home to pay their respects, and Ulysses was distraught.

He went on continue his career as a performer, travelling around the world, and later married Gertrude Curtis, New York’s first black woman dentist. Ulysses ultimately died at the grand old age of 101.

Alva and Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont

Alva and Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont

Alva Belmont first became a prominent New Yorker upon her marriage to William Kissam Vanderbilt. The outspoken, self-possessed socialite shocked society when she divorced Vanderbilt on grounds of adultery, and later married businessman and politician Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont, himself a divorcé. They had met while on a cruise around the world on Mr. Vanderbilt’s yacht, at which time an attraction was already apparent, and were said to “have been seen together almost every day since the divorce.” Their marriage ceremony was small and intimate, and there was reportedly no representative from the Belmont family among the guests.

Oliver died in 1908 of appendicitis, and Alva commissioned the Belmont Mausoleum at Woodlawn as a lasting memorial for both of them. The mausoleum is a replica of the chapel of Saint-Hubert at Amboise in France’s Loire Valley, notably the burial place of Leonardo da Vinci. Within, Oliver is interred on the left, and Alva on the right.

After Oliver’s death, Alva became passionately involved with the movement for woman’s suffrage and is remembered as a major figure of that movement.